The History of Beer III – Medieval Europe 3: Economics

The image of a medieval town tends to revolve around muddy streets, market squares, and the distant call of “Bring out yer dead”. But lurking behind the pox merchants and snake oil vendors was one of the most powerful forces in the economy: beer. Not just a beverage, beer was an economic engine that drove trade, funded cities, empowered guilds—and occasionally left the taxman tipsy.

A Refresher: Home and Away1

In the early medieval period, beer was still largely the domain of households and monasteries. But by the 12th and 13th centuries, things started to scale up. Urban growth and technological improvements meant that brewing could leave the cloister and take up residence in purpose-built breweries.

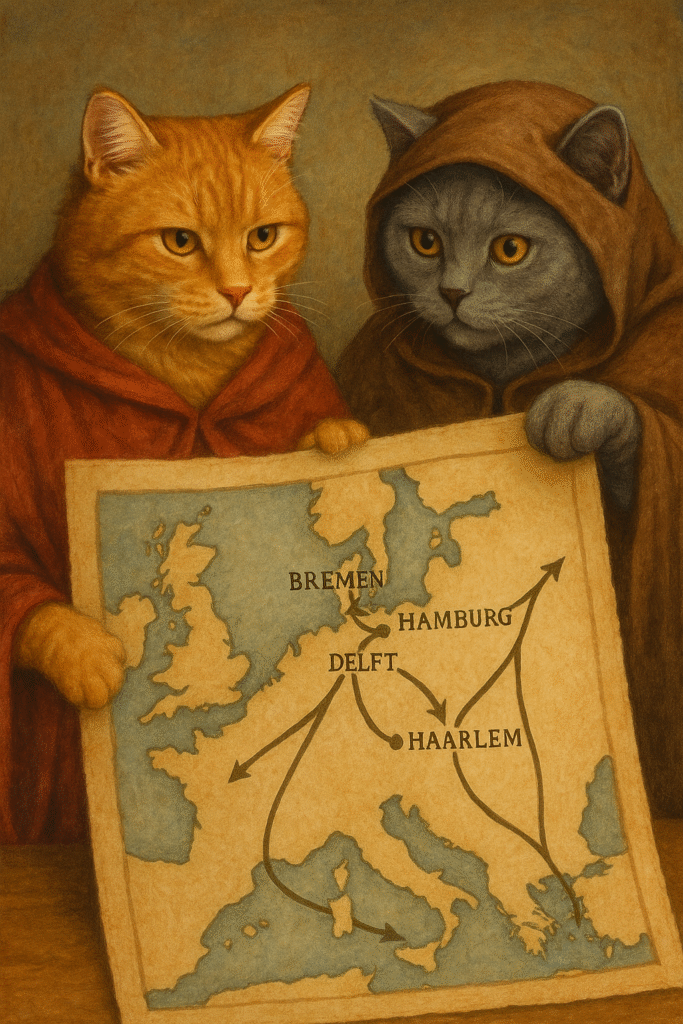

The true game-changer was the widespread use of hops2. Hopped beer kept longer, travelled further, and—crucially—tasted better after a few weeks at sea than the traditional herbal ales. This gave rise to a new wave of commercial brewing aimed squarely at trade. Northern German towns like Bremen and Hamburg became renowned for their hopped brews, shipping their barrels to England, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia. These weren’t just village exports—they were big business. In fact, Douai (in modern-day France) had at least 22 breweries in operation between the 13th and 15th centuries3. That’s one for every 400 people, a ratio that would make many people happy now!

Tax Me Another

With beer production booming, the authorities saw a golden opportunity—through the bottom of a pint glass. Beer taxes quickly became a cornerstone of municipal finance. In some towns, they accounted for up to 20% of indirect tax revenues4. Beer was easy to tax, hard to smuggle, and—best of all—consumed by just about everyone.

And it wasn’t just the beer itself. Tax collectors cast a wide net, charging levies on ingredients like grain, malt, and gruit. The resulting income paid for everything from city walls to public fountains and the occasional hanging. To paraphrase Jefferson Starship, they built their cities on beeeeeer!

The Guilded Age5

As brewing became more profitable, it also became more professional. Enter the brewers’ guilds—formal associations that controlled everything from quality standards to training apprentices. The Brussels brewers’ guild, formally recognised in 1365, even set price controls and ingredient lists, turning beer-making into an early science is just one example. Their mission: protect quality, manage pricing, guard trade secrets, and keep out riffraff

Guilds weren’t just about craftsmanship; they were also political. They negotiated with city governments, lobbied for tax breaks, and controlled who could brew what, where, and when. In many towns, membership was required to legally sell beer, and guild seals served as an early mark of quality long before the existence of ISO.

But power has its price. As brewing scaled up and commercialised, small-scale brewers—especially women—were edged out. Alewives who once dominated local production now found themselves excluded from guilds that required expensive equipment, capital, or social clout; in other words money and connections. Regulation was a double-edged sword: it improved safety and standardisation but also created monopolies and widened economic gaps6.

Beer and the Medieval Marketplace

Beer didn’t just slake thirst—it shaped markets. The rise of long-distance trade meant brewing was no longer about sloshing a few mugs around the parish. It was about logistics, preservation, and scale. And it was international.

Imported beers carried prestige. “Hamburgs” were the gold standard, while English chiervoise became a fashionable foreign drink in parts of France. This drove competition and innovation among local brewers, who either had to level up or lose their market share.

This also meant that beer production could shape a town’s identity. Just as wool defined some towns and salt others, beer became a local pride point—economic and cultural capital in one foamy head.

Final Sip

So, was medieval beer just a cheap drink for peasants? Hardly, as we continue to see, beer was much more than that. It was a vital economic driver, a pillar of tax systems, and a source of political clout. As much as beer helped people survive, it also helped cities thrive.

- Dodgy reference to an old Australian soap opera. ↩︎

- Unger, R. W. (2004). Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. University of Pennsylvania Press. ↩︎

- Nelson, M. (2005). The Barbarian’s Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Routledge. ↩︎

- Epstein, S. R. (2000). Freedom and Growth: The Rise of States and Markets in Europe, 1300–1750. Routledge. ↩︎

- I know, it’s a horrible pun ↩︎

- Bennett, J. M. (1996). Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600. Oxford University Press. ↩︎