The Evolution of Language I: From Grunts to Grammar

“What would dogs do if they could talk? They would bore us all to death with their stories of how loyal they are.”1

Language is the crown jewel of human evolution — or at least the loudest one. From Neanderthal grunts to diplomatic double-speak, it’s the tool we use to share dreams, issue threats, tell jokes, invent gods, and argue about dinner. And yet, for all its centrality, the origins of language remain one of science’s greatest enigmas — a tale whispered across millennia with no written witnesses, only speculative echoes.

So, where did language come from? Not writing (we’ll get to that later), but spoken, signed, and spat-out language: the first real talking. Why do we have it when our closest relatives — the perfectly nice but notably mute chimpanzees — don’t? And can we learn anything useful from a gibbon in heat or a man showing off in a nightclub? More importantly, would we want to?

Let’s begin.

What Makes Language… Language?

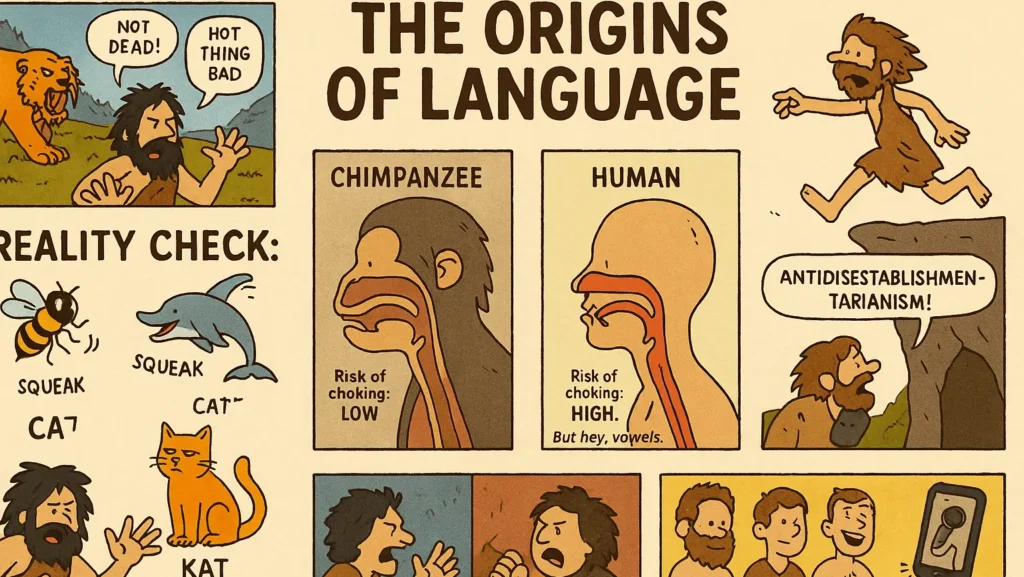

First, a reality check: language is not just noise with meaning in the same way as music is not just noise with tempo. Plenty of animals communicate — bees dance, dolphins squeak, dogs bark, and cats… judge. But what humans have is orders of magnitude more powerful, and crucially, more flexible. We don’t just emit sounds — we mix, match, and rearrange them into infinite combinations with infinite meanings.

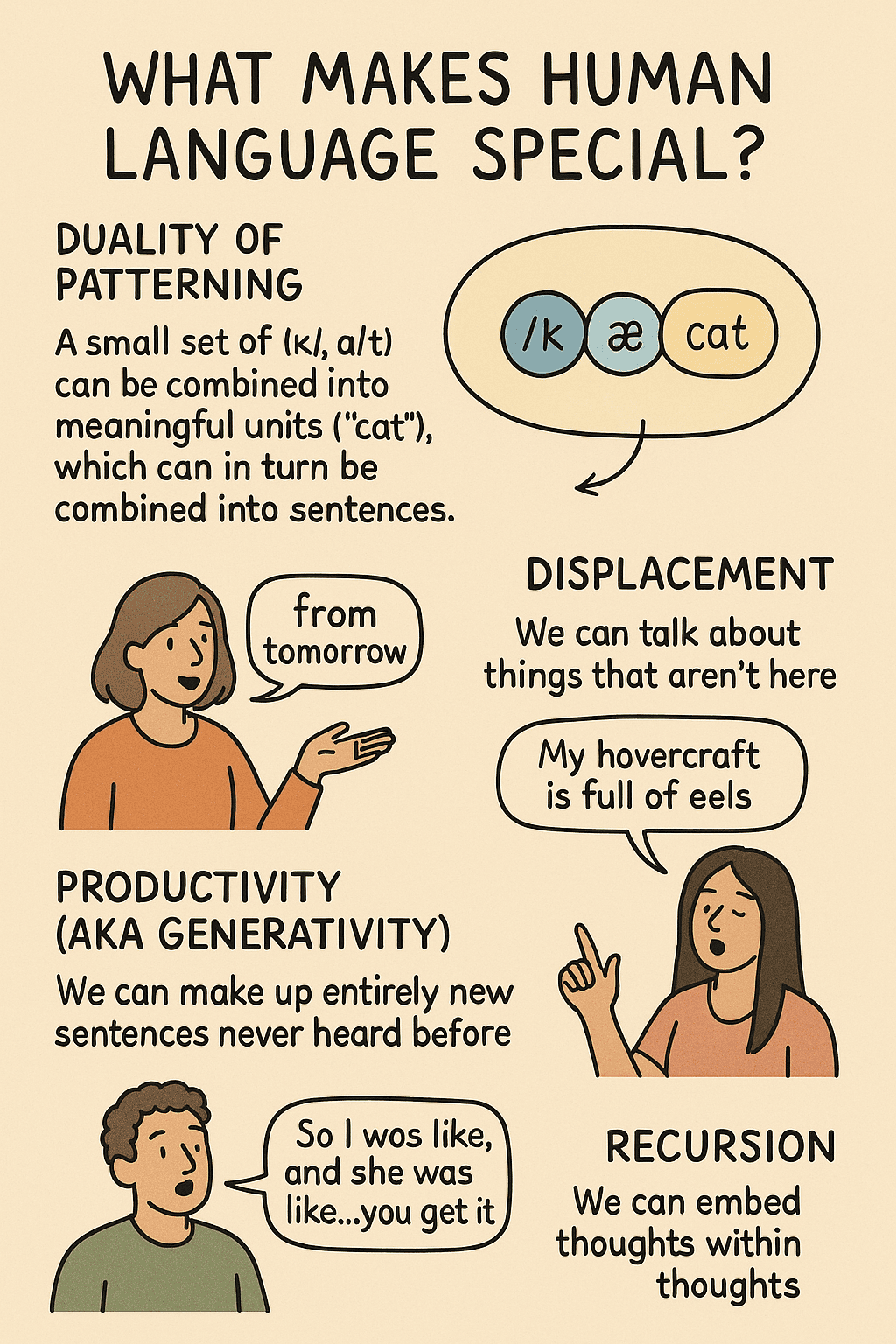

Linguists point to several key features of human language:

– Duality of patterning: A small set of meaningless sounds (like /k/, /æ/, /t/) can be combined into meaningful units (“cat”), which in turn can be combined into sentences.

– Displacement: We can talk about things that aren’t here, like “tomorrow,” “my hopes and dreams,” or “before Covid.”

– Productivity (aka generativity): We can make up entirely new sentences never heard before. (“My hovercraft is full of eels.2”)

– Recursion: We can embed thoughts within thoughts. (“So, I was like, she was like, and then I was like — wait, what were we even talking about?”)

None of these features are fully present in even the smartest animals. Some can learn signs or words (looking at you, Koko3), but they lack the spontaneous, combinatorial inventiveness of a toddler telling an imaginary friend to share their snack, or a drunk trying to order a kebab.

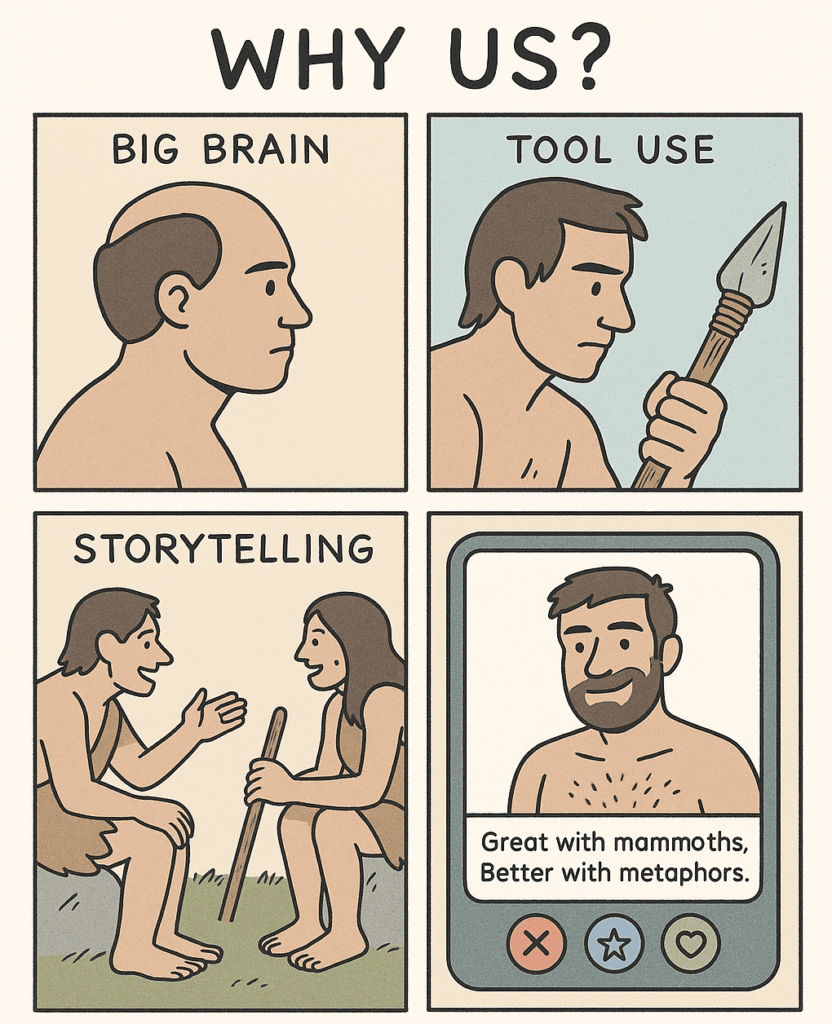

Why Us? Evolution’s Linguistic Leap

Here’s the puzzle: if language is so useful, why don’t all species have it?

The answer, frustratingly, is complicated. Evolution doesn’t hand out prizes for “most eloquent.” Language likely developed in humans because a whole package of traits came together: big brains, long childhoods, social living, and maybe a touch of vanity.

There are several theories:

– The Social Grooming Hypothesis (Dunbar): In large social groups, gossip replaced grooming as a way to build bonds. Words are cheaper than picking lice.4

– The Tool Coordination Theory: Working together required complex planning — and instructions. (“You hold the mammoth’s leg; I’ll hit it with a rock.”)5

– The Sexy Peacocks Theory: Language as a display trait — those who could tell clever stories were more attractive. (This theory may explain poetry, rap battles, why some men on dating apps list “banter” as a skill, and Dudley Moore).6

And of course, once the snowball got rolling, there was no stopping it. Language made culture possible, which in turn selected for better language. Fire, fables, farming — all required us to name, recall, and discuss things far removed from the here-and-now.

From Gestures to Grumbling (and Back Again)7

So, did we start out as mime artists or mumblers? Please let it be mumblers, the idea of descending from mime artists is abhorrent. In this respect I am much like Terry Pratchett’s Lord Vetinari.8

One major debate in language origin studies is whether gestures or vocalisations came first. Some scholars argue that early humans relied on elaborate manual signals, much like modern-day sign languages or what you do when trying to get someone’s attention in a noisy pub. These gesture-first theories9 point out that:

– Primates gesture more flexibly than they vocalise

– Sign languages are just as rich and expressive as spoken ones

– Hands are easier to control consciously than vocal cords

Others, however, champion a vocal-first view.10 After all, speech doesn’t require line of sight, works in the dark, and leaves your hands free for other things — like throwing spears, holding tools, or dramatically gesturing while arguing about whose turn it is to hunt.

But the more likely truth is that language emerged from a mix of both.11 Our ancestors were probably gesturing and grunting their way through the Pleistocene like an overcaffeinated game of charades. Over time, with better breath control and brain wiring, those grunts got grammar, and the hand waving got context.

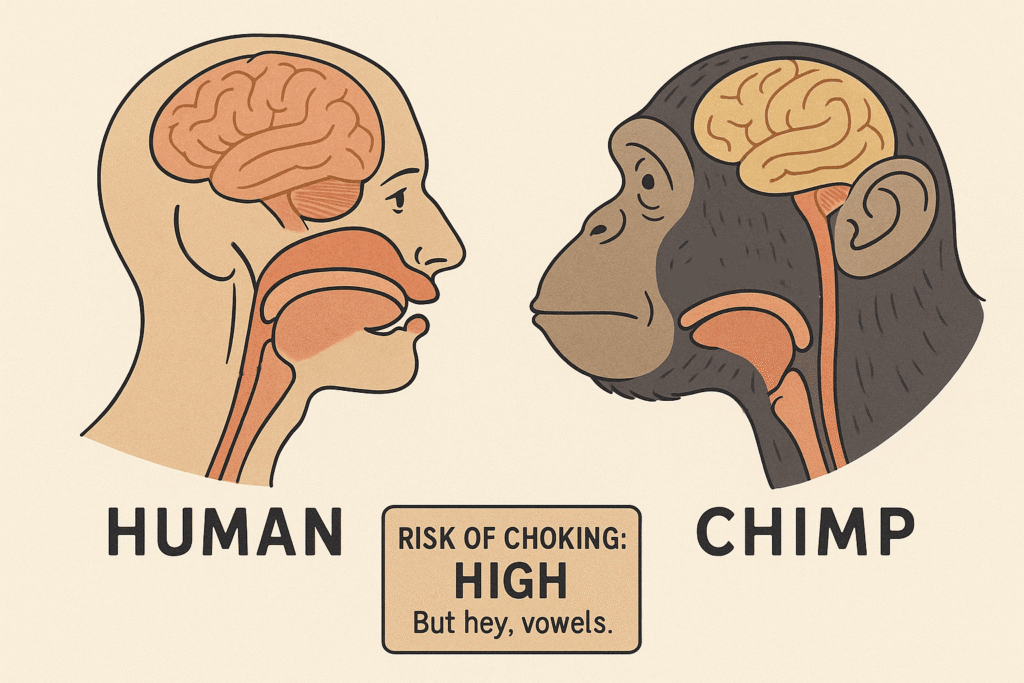

Brains, Breath, and the Big Risk of Choking

Human speech is an evolutionary miracle — and a choking hazard.

To produce language, we had to make some very risky biological upgrades:

– Descended larynx – Allows a wider range of sounds, but makes it easier to choke on food. Evolution said: “Let them risk death for the perfect vowel.”

– Flexible tongue and lips – Great for consonants, also great for sticking out at annoying siblings.

– Specialised brain areas – Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area handle the grammar and meaning of speech, while other bits handle the memory, emotion, and social messiness of it all.

Even more astonishing is that our brains come pre-loaded with a language acquisition engine12 — children don’t need explicit grammar lessons to learn how to speak. They absorb it from context, much like teenagers pick up gossip or interesting blisters.

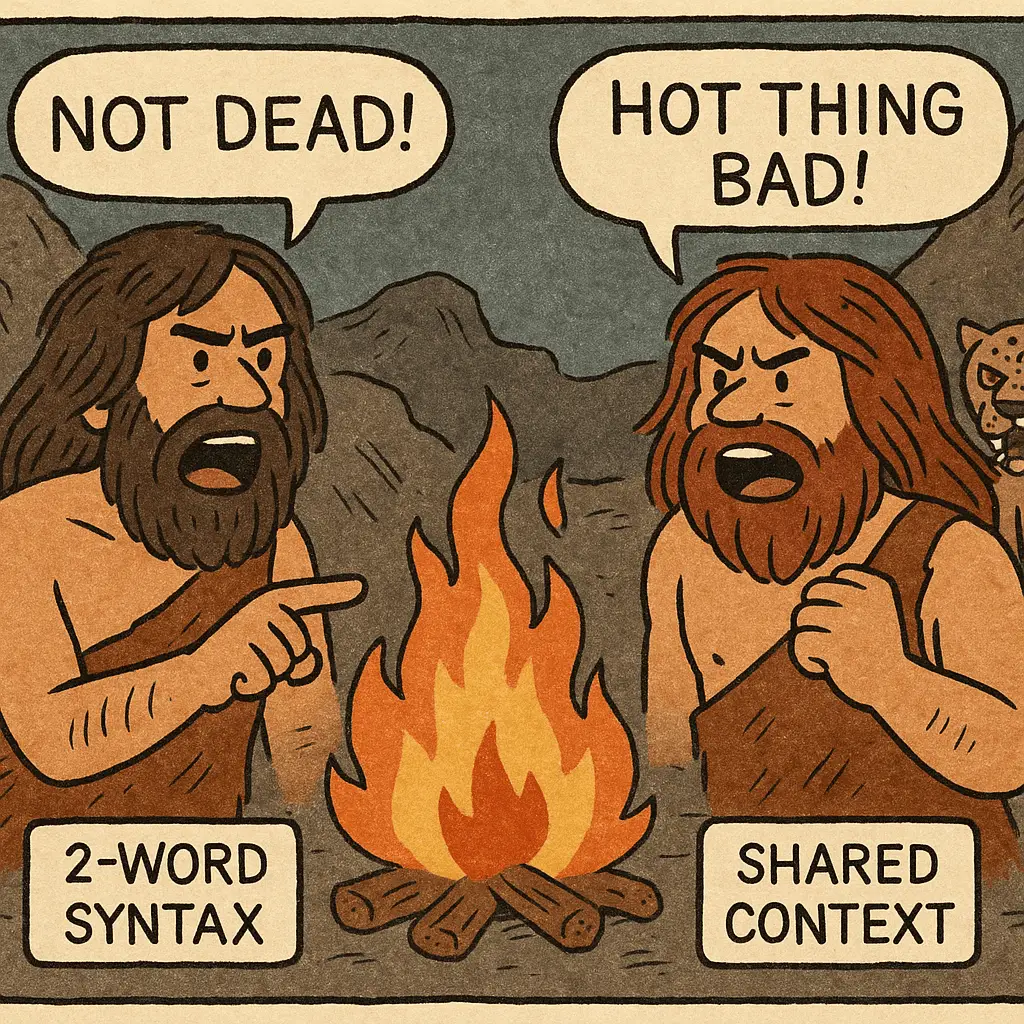

Proto-Language: The First Chatter

Let’s imagine the first conversations.

They probably weren’t philosophical debates or romantic sonnets. More likely they were things like:

– Here. Hare. Here.13

– You help.

– Not dead!

– Hot thing bad.

This early proto-language might have lacked complex grammar but was rich in context and shared understanding. Linguist Derek Bickerton proposed that proto-language consisted of two-word utterances and a vocabulary of perhaps 100–200 items.14 It was enough to share intentions and point at things together — which, when you think about it, is 90% of early parenting and 60% of Instagram.

Language likely bootstrapped itself: words → combinations → syntax → recursion, in the same way as The Great British Bake Off evolved from a simple cooking show into a multi-series beast featuring Torta Setteveli and tantrums.

What Was the First Word?

Was it “Mama”? “Fire”? “Ow”?

We’ll never know. But it probably wasn’t “defenestration” or “antidisestablishmentarianism.” It was probably something deeply practical, possibly shouted at a friend right before they walked into a sabretooth.

What we do know is that once language took off, it spread quickly. Different groups, isolated or migrating, began tweaking and remixing their shared words like Tricky and Portishead with one sample between them15. Over thousands of years, this gave rise to everything from the precision of Japanese to the chaotic brilliance of English.

Having started with the birth of language, it only makes sense to turn our attention to “Mother Tongues and Family Trees” next when we’ll find out the answer to questions like:

Why does Persian sound nothing like English, even though they’re distant cousins?

What’s a proto-language?

And who keeps naming things “Indo-European”?

- Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power, trans. Carol Stewart (London: Gollancz, 1962), 367. ↩︎

- “Dirty Hungarian Phrasebook” sketch, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, episode 25, first aired 16 November 1970, BBC. ↩︎

- https://www.koko.org/about/programs/project-koko/interspecies-communication/sign-language/ ↩︎

- Oxford University profile of Dunbar’s Grooming Hypothesis ↩︎

- Stout & Chaminade, “Stone tools, language and the brain in human evolution” – Philosophical Transactions B (2012) ↩︎

- Geoffrey Miller, The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature (New York: Doubleday, 2000). ↩︎

- One of Tolkien’s lesser-known works ↩︎

- “It was said that [Vetinari] would tolerate absolutely anything apart from anything that threatened the city… And mime artists. It was a strange aversion, but there you are. Anyone in baggy trousers and a white face who tried to ply their art anywhere within Ankh’s crumbling walls would very quickly find themselves in a a scorpion pit, on one wall of which was painted the advice: Learn The Words.” ― Terry Pratchett, Guards! Guards! (London: Gollancz, 1989). ↩︎

- Corballis, M. C. (2002). From hand to mouth: The origins of language. Princeton University Press. ↩︎

- Fitch, W. T. (2000). The evolution of speech: A comparative review. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(7), 258–267. ↩︎

- Tomasello, M., & Zuberbuhler, K. (2002). Primate vocal and gestural communication. In A. Collin, M. Bekoff, & GM. Burghardt (Eds.), The cognitive animal (pp. 293-299). MIT Press. ↩︎

- Noam Chomsky’s theory of a Language Acquisition Device (LAD) posits that humans are biologically predisposed to acquire language. See SimplyPsychology summary or Chomsky, Reflections on Language (1975). ↩︎

- Bruce Robinson, Withnail and I: The Original Screenplay (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000). ↩︎

- Wikipedia overview of Proto-Language theory ↩︎

- “Hell is Round the Corner” by Tricky, and “Glory Box” by Portishead both used the same sample from Isaac Hayes’s “Ike’s Rap II” and were released around the same time. Allegedly Tricky was forced to delay the release of his song to ensure the success of Portishead’s. ↩︎

P.S. Curiously, languages that sound beautiful when spoken often birth musical genres that should come with a warning label, and vice versa. Yes, French and German, I am looking at you.