The Evolution of Language III: Borrowed Tongues — How Languages Mingle, Mix, and Make Mischief

The Linguistic Thieves’ Bazaar

Languages don’t grow in isolation. They flirt, trade, intermarry, steal from each other, and sometimes wake up speaking with a new accent. While the previous article traced the slow branching paths of descent — from proto-languages to modern tongues — this chapter deals with the chaotic horizontal traffic of vocabulary and influence. Not so much family tree as conspiracy theory at a MAGA meet.

English is the most infamous magpie: a Germanic base layered with Norman French, Latin, Greek, Old Norse, Hindi, Japanese, Arabic, Yiddish, and more. Its vocabulary is less a tidy inheritance than a multilingual ransom note.

But English isn’t alone. From Swahili to Japanese, Turkish to Tagalog, languages the world over have absorbed and adapted foreign words. This article explores how — and why — that happens. We’ll look at the mess and magic of linguistic cross-pollination: the ways people smuggle words across cultural borders, tweak them to fit new rules, and sometimes misunderstand them entirely.

“English doesn’t borrow from other languages. English follows other languages down dark alleys, hits them over the head, and rifles through their pockets for loose vocabulary.” —James Nicoll (popularly attributed)

Linguistic Borrowing as Cultural History

Linguistic borrowing isn’t just a matter of vocabulary. It’s a living record of who spoke to whom, and under what circumstances — trade, conquest, religion, intermarriage, or sheer cultural curiosity. Every borrowed word is a souvenir of historical contact1.

Take the Arabic influence on Spanish. After 800 years of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula, Spanish still carries hundreds of Arabic-origin words: almohada (pillow), aceituna (olive), naranja (orange), azúcar (sugar), and even ojalá (“hopefully”) from in shā’ Allāh (“if God wills”).

Or consider Swahili, a Bantu language heavily shaped by centuries of Indian Ocean trade. Its vocabulary is a rich blend of Arabic (kitabu = book), Persian (shule = school), Portuguese (meza = table), Hindi (chai = tea), and English (penseli = pencil). Swahili’s very name may come from the Arabic word sawāḥil (coasts)2.

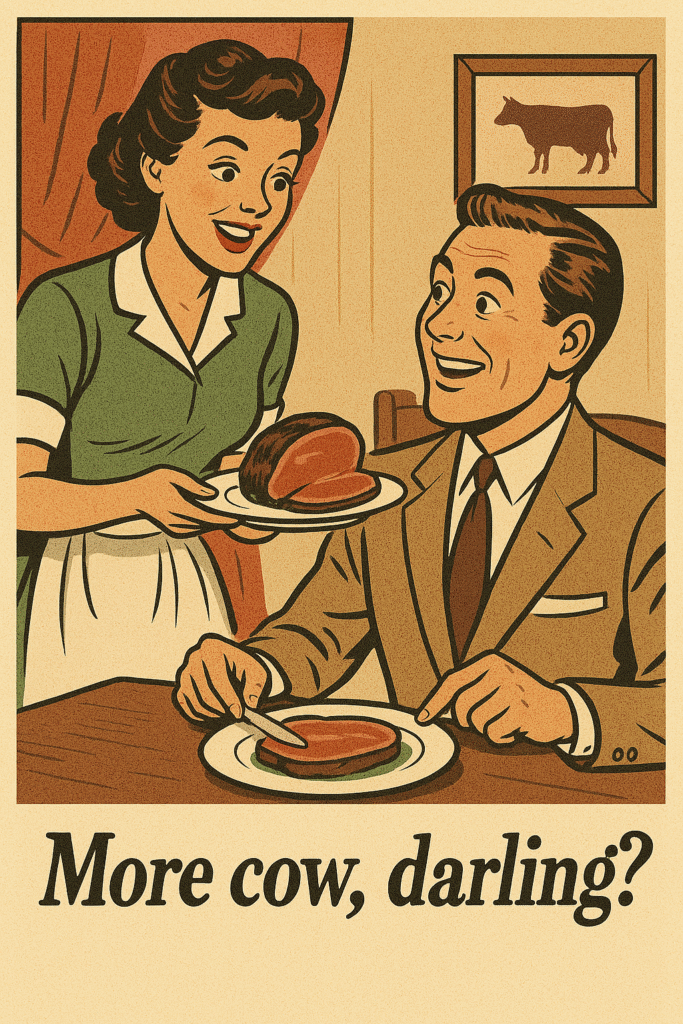

Borrowing also reflects prestige — which language was seen as “finer,” “smarter,” “more elite.” This is especially clear in English, where the Norman Conquest of 1066 introduced a lasting social divide between Anglo-Saxon peasants and French-speaking nobility.

Nowhere is this more apparent than at the English dinner table. We raise cows (Old English cū, cf. German Kuh) and pigs (pigge, cf. German Schwein), but we eat beef (French bœuf) and pork (French porc)3. Similarly, sheep gives way to mutton (mouton) once it’s on the plate. The animals kept their Anglo-Saxon names — because that’s what the farmers called them — but their meat took on the French terms used in aristocratic kitchens.

| Animal (OE/Germanic) | Meat (French/Latinate) |

| Cow | Beef (bœuf) |

| Pig | Pork (porc) |

| Sheep | Mutton (mouton) |

| Deer | Venison (veneson) |

This culinary code-switching reveals a deep social reality. For centuries after the conquest, English was the language of the fields and hearths, while French ruled the courts, kitchens, and cathedrals. The legacy is still in our lexicon — not just for food, but in law (justice, jury, court), fashion (gown, attire), and etiquette (honour, courtesy).

Prestige borrowing also shaped the academic lexicon. During the Renaissance, scholars in Britain and Europe began importing Latin and Greek terms en masse — not just because they were classical, but because they conferred intellectual credibility (remember Caius from the previous chapter?). Hence philosophy, biology, climate, theatre, and hydraulic.

But prestige is fluid. In the 20th century, English became the prestige donor — especially in pop culture, tech, and branding. From Franglais (French advertising copy laced with English) to Konglish (Korean-English hybrids), we now see a reversal: languages borrowing English for cool, innovation, or global clout — even when a perfectly good native term already exists.

The Many Ways to Borrow a Word

Borrowing isn’t monolithic. Linguists distinguish multiple types of borrowing, each with its own quirks and pathways. Here’s a closer look at the main categories:

1. Loanwords

The most straightforward kind. A word is taken wholesale — with minor phonetic adaptation — and inserted into the new language. Examples:

• Sushi, karaoke, anime[15] (from Japanese)

• Robot (Czech)

• Piano, opera (Italian)

• Algebra, alcohol (Arabic) [Durkin, 2014]

Loanwords often cluster around new concepts, technologies, or cultural items — you don’t invent your own term for “sushi” when the Japanese version comes neatly packaged.

2. Calques (Loan Translations)

Rather than importing the word, the new language translates each part literally. For example:

• Skyscraper → French gratte-ciel (“scrape-sky”)

• Flea market → German Flohmarkt

• Superman → German Übermensch

We’ll explore these more fully a little lower down the page.

3. Loanblends and Hybrids

Sometimes a borrowed word gets glued to a native suffix or prefix:

• Drinkeria (mock Spanish for a trendy bar)

• Teppan-yaki + burger → teppanburger

Note these are not examples of portmanteaus. Brangelina, David Cameron’s proclivity for “chillaxing”, and sporks have nothing to do with this. For more about word formation, see Crystal, 20034.

4. Pseudo-loans

Words that look like they come from another language — usually English — but were actually coined domestically. In Japanese, these are known as wasei-eigo (“Japan-made English”), and we’ll see more soon.

5. Semantic Loans

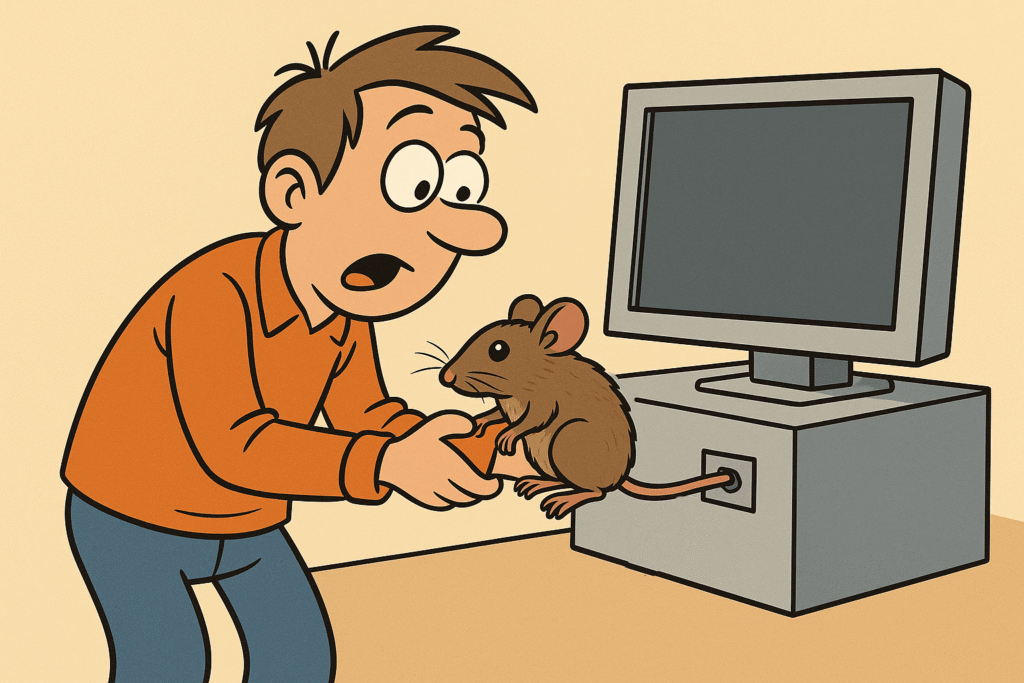

Where a native word takes on a new borrowed meaning:

• English mouse (animal) became mouse (computer device)

• French ordinateur (computer) influenced the use of ordenador in European Spanish

As Philip Durkin notes, loanwords aren’t just about sound — they often involve the borrowing of concepts, meanings, or entire idioms. In other words, “languages steal meanings, too — and sometimes the words don’t even notice.”

Boomerang Words and Back-Loan Shenanigans

Some borrowed words don’t stay borrowed — they come back home wearing new clothes. These are boomerang words: terms that make a round-trip journey through multiple languages, often changing meaning or form along the way.

Consider restaurant. It began life as the Latin verb restaurare, meaning “to restore.” In 18th-century France, it was adopted as restaurant, a place to restore one’s strength with food. From there, it entered English and then made its way into countless languages: Spanish (restaurante), German (Restaurant), Turkish (restoran), Japanese (resutoran). Its global spread reflects not just the word’s usefulness, but the spread of the cultural concept it names.

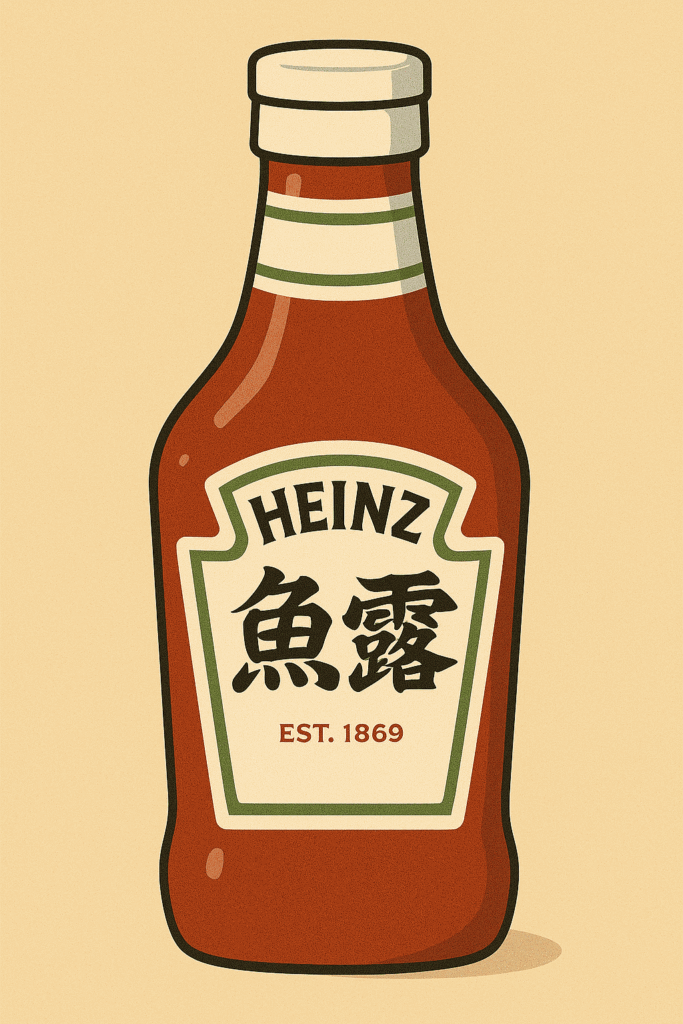

Even more dramatic is ketchup. Its distant ancestor was kê-tsiap5, a fermented fish sauce from Southern China, spread via Malay and Hokkien traders. The British encountered it in Southeast Asia and brought it home, adapting it into a tangy sauce made with mushrooms, then finally tomatoes. Modern American ketchup shares little but the name with its umami-rich forebear — and now ketchup is found on labels across Asia, where it originally came from.

A subtler example is pyjamas (US: pajamas), from the Persian pāy-jāmeh (literally “leg garment”), adopted via Urdu into English during the British Raj. In English, it narrowed in meaning to sleepwear — and in some countries it has since been re-borrowed with that restricted definition, despite the original Persian usage having nothing to do with bedtime.

These word journeys aren’t just fun linguistic trivia. They reflect the flow of power, trade, colonisation, and pop culture. In today’s digital world, the boomerang effect [Haspelmath, 2009] is even faster: a meme word coined in English might be adopted in Korean, remixed, and fired back globally with new connotations in days.

L’Exception Française—and Its Cousins

While many tongues welcome borrowed words with open arms, some nations treat them more like unwanted intruders. The motivations vary—cultural pride, fear of imperialism, or the forging of national identity—but the result is the same: policies, watchdogs, and some very inventive vocabulary.

France: Vive la Pureté

Perhaps the most famous language guardians are the members of the Académie Française, founded in 1635 to preserve the purity of French. The Académie has long promoted native alternatives to foreign terms: courriel (email), logiciel (software), and mot-dièse (hashtag) are just a few examples. Although many of its prescriptions are ignored in everyday speech, it still wields legal influence through the Loi Toubon, passed in 1994. The law mandates the use of French in public signage, government communication, product labeling, and workplace documentation, especially when intended for the general public or employees in France6.

This linguistic protectionism is rooted in centuries of perceived cultural encroachment, especially from English in global media, business, and technology.

Quebec: Even More Francophone Than France

In Quebec, the impulse to protect French runs even deeper. The Charter of the French Language—better known as Bill 101—was enacted in 1977 and makes French the official language of the province. It governs education, business, signage, and employment, requiring French to be “markedly predominant” on public signs and ensuring French-language services across all sectors7.

Interestingly, Quebec French often adopts native alternatives more consistently than France itself. While le weekend is commonly used in Paris, Quebec prefers fin de semaine. Other homegrown inventions include courriel (email), clavardage (online chatting), and balado (podcast). The motivation isn’t just cultural—it’s existential. Quebec sits in an English-speaking sea, and for many, language preservation is tied to identity and political autonomy8.

Iceland: Wordsmiths of the North

Iceland is known for its linguistic conservatism and inventive purism. Instead of importing foreign terms, Icelanders typically coin new ones from Old Norse roots. Computer becomes tölva, a blend of tala (number) and völva (prophetess). Telephone is sími[17], a repurposed old word meaning “wire.” These efforts are supported by the Icelandic Language Council and the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, which regularly propose and promote native alternatives9.

Despite the increasing influence of English, especially among young Icelanders, the small, literate, and proud population has largely embraced the policy. Language preservation is tied to cultural heritage and even national tourism branding.

Israel: Revival with Boundaries

Modern Hebrew is a unique case: a revived ancient language that had not been a mother tongue for centuries. Spearheaded by figures like Eliezer Ben-Yehuda in the late 19th century, Hebrew had to be radically expanded to suit modern life. Thousands of new words were coined from Biblical, Talmudic, or other Semitic roots10. The Academy of the Hebrew Language, established in 1953, continues this work, publishing dictionaries, approving neologisms, and setting official grammar standards. Still, linguistic purity is a moving target. English terms, especially in science, business, and pop culture, often slip into everyday Hebrew. While some neologisms catch on, many native speakers use hybrids, anglicisms, or slang without much concern11,12.

TL;DR: The Language Police, Worldwide

| Country | Institution | Strategy | Legal Backing | Success Rate |

| France | Académie Française | Replace English loans with French alternatives | Toubon Law | Medium (official docs yes, daily speech no) |

| Quebec | OQLF (Office québécois de la langue française) | Strict signage & workplace laws; promote French equivalents | Charter of the French Language | High in public life, variable in youth/pop culture |

| Iceland | Icelandic Language Council | Coin new Icelandic terms from native roots | Advisory, but widely followed | High cultural buy-in |

| Israel | Academy of the Hebrew Language | Revive and modernize Hebrew with native coinages |

English: The Lexical Car Boot Sale

Have you ever been to a car boot sale, or even just a charity shop? They’re full of unrelated items that you somehow feel you need to improve your life. The English language feels like that about the rest of the world. English may be the global champion of linguistic borrowing (or theft) — not just in volume but in audacity. It doesn’t just welcome/steal foreign words; it builds its identity from them. The result is a language that’s both incredibly rich and structurally incoherent.

Start with the bones: Old English, a Germanic language, brought us core vocabulary like man, woman, earth, water, and house. Then came the Vikings, who added Norse verbs like take, call, get, and die. Their presence also helped simplify English grammar, encouraging a more analytical structure.

Then came 1066, and with it, the Normans. French-speaking aristocrats imposed not just political rule but linguistic overlay: castle, court, govern, judge, feast, supper, beef. As discussed earlier, the peasantry kept saying cow and pig — but the menus changed to beef and pork.

The Renaissance ushered in a tidal wave of Latinate and Greek vocabulary, especially in science, philosophy, and the arts. Philosophy, anatomy, climate, theatre, and hydraulic are all examples.

The result is a lexicon layered like geological strata:

- Ask (Old English)

- Question (Norman French)

- Interrogate (Latin via French)

| Register | Example | Origin |

| Basic | Ask | Germanic (Old English) |

| Formal | Question | French |

| Technical | Interrogate | Latin |

This triplicate layering gives English a flexibility of tone and nuance few other languages can match — but it also makes spelling unpredictable, synonyms subtle, and grammar full of exceptions. Even within a single sentence, English speakers toggle between Germanic bluntness and Latin flourish — often unconsciously. This makes English vocabulary rich, nuanced… and incredibly inconsistent. This smorgasbord (stolen from the Swedes) is also why English lends itself so well to puns, double meanings, and wordplay — a gift for poets and a nightmare for translators.

“English is not a language. It’s three languages in a trench coat pretending to be one.”

Widely attributed to a Tumblr user named grelber.

This chaotic evolution also explains why English speakers are unusually comfortable with foreign loanwords: piano(Italian), yoga (Sanskrit), sushi (Japanese), algebra (Arabic), anorak (Inuit), marmalade (Portuguese), and kindergarten(German), to name a few.

And thanks to its colonial history and modern cultural dominance, English is now not just a borrower, but a global donor language13 — feeding into Korean, Japanese, French, Hindi, Spanish, and more, often with strange results. Which brings us to…

Japan and the Katakana Empire

No language has turned borrowing into an art form quite like Japanese. It doesn’t just import words — it domesticates them, transforms them, and stamps them with linguistic visa status using an entire writing system: katakana.

Unlike kanji (used for native content words) and hiragana (used for grammatical endings and native phonetics), katakana is visually distinct and reserved primarily for foreign loanwords (gairaigo), onomatopoeia, brand names, and emphasis. Think of it as Japan’s official script for imports — a kind of linguistic quarantine zone.

So when the English word ice cream becomes アイスクリーム (aisukurīmu), or personal computer becomes パソコン (pasokon), katakana marks the term as foreign… but now fully Japanese.

Some borrowed words retain their meaning (banana, hotel), while others undergo spectacular shifts. Consider:

- Mansion (manshon): Not a palatial estate, but a modest apartment complex.

- Smart (sumāto): Slim or stylish, not intelligent.

- Consent (konsento): An electrical outlet. From concentric plug, nothing about the outlet consenting.

- Tension (tenshon): A high-energy, positive mood — e.g., “Let’s keep the tension up!”

There’s even a term for English-sounding words coined in Japan: wasei-eigo (和製英語, “Japan-made English”)[8]. These often baffle native English speakers:

- Salaryman: A white-collar office worker

- OL: Office Lady (used for female clerical staff)

- Freeter: A part-time worker or freelancer

- Baby car: Pushchair or pram – I actually caught myself using this one the other day, or near enough, I said baby carriage.

While some purists criticize this linguistic bricolage, others embrace it as a sign of cultural creativity. Japan doesn’t just borrow — it rebrands.

And sometimes, the loans come full circle. Terms like anime, karaoke (kara = empty, ōke = orchestra), cosplay, and emoji have entered global English — returning to their roots with new meanings and audiences.

Top 10 Japanese Loanwords You Didn’t Know Were Foreign (and Vice Versa)

Part 1: Japanese Loanwords in English

These words are used so commonly in English that many speakers are unaware of their Japanese origins.

Tycoon

Origin: From the Japanese word taikun (大君), meaning “great lord” or “shogun.” It was used in the 19th century by foreigners to refer to the leader of Japan. Today, it’s used to describe a powerful business magnate, with most speakers having no idea of its connection to samurai-era Japan.

Hunky-dory

Origin: While debated, a leading theory suggests this phrase originated from a street in Yokohama, Japan, named Honchō−dōri (本町通り). American sailors in the 1860s frequented this street and are thought to have corrupted its name into “hunky-dory” as slang for “all is well” or “satisfactory.”

Skosh

Origin: A quintessential piece of American slang meaning “a small amount.” It comes directly from the Japanese word sukoshi (少し), which means “a little.” The word was adopted by American soldiers during the post-WWII occupation of Japan.

Emoji

Origin: This word seems intrinsically linked to “emotion,” but that’s a coincidence. It’s a pure Japanese compound of e (絵, “picture”) and moji (文字, “character”). The global rise of Japanese mobile phone culture in the late 1990s brought the word and the concept to the world. 😲 as the youth would say.

Soy

Origin: This staple food word is so fundamental to English kitchens that its foreign roots are easily forgotten. It comes from the Japanese word for soy sauce, shōyu (醤油).

Part 2: Foreign Loanwords in Japanese (Gairaigo)

Known as gairaigo (外来語), foreign loanwords are a massive part of modern Japanese. The following words are so deeply integrated that many Japanese speakers don’t think of them as foreign.

Arubaito (アルバイト)

Meaning: Part-time job.

Origin: This word does not come from English, but from the German word Arbeit, meaning “work.” It’s an essential term for students and anyone seeking supplemental income in Japan, and it feels completely Japanese.

Pan (パン)14

Meaning: Bread.

Origin: Bread was introduced to Japan by Portuguese traders in the 16th century. The word comes directly from the Portuguese pão. As one of the earliest and most basic loanwords, its foreign origin is rarely considered in daily conversation.

Sararīman (サラリーマン)

Meaning: A salaried office worker.

Origin: While the components are English (“salary” + “man”), this compound is a Japanese invention, or wasei-eigo (和製英語). The term carries a unique cultural weight and describes a specific Japanese social archetype that doesn’t directly translate back into English, making it feel distinctly Japanese.

Konsento (コンセント)

Meaning: An electrical outlet/socket.

Origin: This is a classic example of a loanword that would mystify an English speaker. It comes from the English term “concentric plug,” a type of early electrical fitting. The word was adopted and shortened, and now konsento is the standard Japanese word for the wall socket you plug your devices into.

Hotchikisu (ホッチキス)

Meaning: Stapler.

Origin: This word is the genericized trademark of the E. H. Hotchkiss Company, an early American manufacturer of staplers. Much like “Kleenex” for tissues or “Hoover” for vacuums in English, Hotchkiss became the default word for the object itself in Japan.

Japan’s linguistic strategy is pragmatic and playful. It absorbs what it wants, reshapes it to fit Japanese phonotactics, and marks it clearly. In doing so, it reminds us that language is not just communication — it’s design.

Dangerous Liaisons: When Borrowing Gets Awkward

We’ve previously taken a brief look at false friends — words that look familiar across languages but mean very different things (e.g., gift in English = present; in German = poison). But here we’ll explore how borrowing, mistranslation, and digital overconfidence can lead to linguistic chaos.

Sometimes it’s the dictionary’s fault. Sometimes it’s ours.

Take the classic case of embarazada. An English speaker might assume it means “embarrassed.” It doesn’t. It means pregnant — a potentially catastrophic misunderstanding.

Or the word preservative. In English, it’s something you add to food. In French, préservatif means condom. Confusing the two can liven up any dinner party.

But not all errors are lexical. Sometimes the grammar or usage context breaks down. Translation tools — while improving — still struggle with nuance, polysemy, and idioms. Literal translations often go hilariously (or dangerously) wrong.

Whilst this is not the best example of this problem, it is all that comes to mind. When I was around 9 or 10, a friend at school mistranslated roundabout (the traffic circle kind) into French as manège — meaning carousel. It was a dictionary lookup gone wrong. As this occurred at an English prep school, he was mocked mercilessly by our teacher, who was probably pretty bad at French himself!

This kind of error — relying on a single, out-of-context dictionary definition — is especially common among language learners and AI translation apps. Words often have multiple meanings, and their correct usage depends on syntax, collocations, and culture.

Even native speakers trip up. In German, Chef means boss, not cook (as it does in French too, it simply means chief15). In French, smoking refers not to cigarettes, but to a dinner jacket (from smoking jacket instead of dinner jacket). And in English, we describe a “gifted child,” while in German, a begabtes Kind might be gifted — but hopefully not toxic.

When languages borrow, meanings often slip. The result can be amusing, confusing, or deeply telling. These “errors” reflect the sheer complexity of human language — and how poorly it fits into simple one-to-one correspondences.

What on Earth is: a Calque

Unlike loanwords, which keep their original shape (pizza, bazaar), calques translate the components of a foreign word or phrase literally. They’re stealthy — they feel native, even when they’re not.

| Concept | Source Term | Calque |

| Skyscraper | English | French gratte-ciel |

| Flea Market | German Flohmarkt | French marché aux puces |

| Superman | German Übermensch | English superman |

| Beer Garden | German Biergarten | English beer garden |

| Brainwashing | Chinese xǐnǎo (洗腦 “wash brain”) | English brainwash16 |

Some calques are elegant. Others are awkward (looking at you, gratte-ciel). And some are so seamless we forget they were ever borrowed. Consider skyscraper itself — a compound of “sky” and “scrape,” a word that now feels quintessentially English, even though its structure echoes French and German models.

Calques remind us that borrowing isn’t always audible17. Sometimes languages copy ideas, not sounds. And in doing so, they disguise the very act of imitation.

Wrap-up: From Pillage to Pastiche

If descent shows where languages came from, borrowing shows how they live. They swap clothes, steal idioms, reinvent meanings, and grow stronger through cross-pollination.

Purists may fret about linguistic “contamination,” but history shows that borrowing is not only inevitable — it’s often creative, adaptive, and joyously irreverent.

A pidgin becomes a creole. A dialect becomes a language. A noun becomes a verb18. A fish sauce becomes ketchup. And your childhood mistranslation of roundabout turns into an anecdote about the absurdity of dictionary dependency.

Whether through conquest, trade, media, or memes, the world’s languages are always mingling. In the global bazaar of speech, everyone’s a little bit of a thief — and that’s what keeps the inventory interesting.

- Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. Mouton, 1953. ↩︎

- Haspelmath, Martin. “Loanword Typology: Steps Toward a Systematic Cross-Linguistic Study of Lexical Borrowability.” Linguistic Typology, 2009. ↩︎

- Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford University Press, 2014. ↩︎

- Crystal, David. English as a Global Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ↩︎

- https://www.etymonline.com/word/ketchup ↩︎

- Loi n° 94-665 du 4 août 1994 relative à l’emploi de la langue française. Légifrance. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000722163 ↩︎

- Office québécois de la langue française. (n.d.). Charter of the French Language[2]. Gouvernement du Québec. https://www.oqlf.gouv.qc.ca/charte/charte_index.html ↩︎

- Bourhis, R. Y. (2001). Reversing Language Shift in Quebec. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? (pp. 101–141). Multilingual Matters. ↩︎

- Hilmarsson-Dunn, A. (2006). Language policies and linguistic diversity in Scandinavia and the Baltic States. In M. Barni & G. Extra (Eds.), Mapping Linguistic Diversity in Multicultural Contexts (pp. 65–78). De Gruyter. ↩︎

- Hilmarsson-Dunn, A. (2006). Language policies and linguistic diversity in Scandinavia and the Baltic States. In M. Barni & G. Extra (Eds.), Mapping Linguistic Diversity in Multicultural Contexts (pp. 65–78). De Gruyter. ↩︎

- Fellman, J. (1973). The Revival of a Classical Tongue: Eliezer Ben Yehuda and the Modern Hebrew Language. The Hague: Mouton. ↩︎

- Zuckermann, G. (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ↩︎

- Kachru, Braj B. The Alchemy of English: The Spread, Functions, and Models of Non-native Englishes. University of Illinois Press, 1990. ↩︎

- https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/E-Magazine-Feb-2023-Bread.html ↩︎

- To be clear, while in French chef indeed means “chief” or “boss”, chef de cuisine is “head cook.” ↩︎

- I have insisted far too many times that the English term came first, but apparently, I’m wrong. Sorry… ↩︎

- Trask, R. L. Language: The Basics. Routledge, 1999. ↩︎

- Thomason, Sarah G., and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. University of California Press, 1988. ↩︎