Time-Travel, Subtitles, and the Great Linguistic Plot Hole: English vs. Chinese Across the Centuries

Why Shakespeare would sound like a stranger, and a Tang scholar might ask you to write instead.

If Hollywood were honest, time-travel films would come with historical linguistics consultants and emergency subtitles.

In films, a 12th-century Londoner lands in 2025 and speaks immaculate modern English. In reality, they’d sound like a Viking gargling porridge. English has changed so much that modern audiences would need subtitles. How does that compare to Chinese, specifically for a modern Mandarin speaker in Taipei as I’m based there, encountering the Chinese of the 5th or 15th century? What would happen if a Tang dynasty poet was dropped into central Xinyi district?

Well, the short answer is, he’d listen uncomprehendingly to modern Chinese before handing over a conveniently carried brush and asking people to write it, not say it, for while English has reshaped both its speech and its standard writing several times, Chinese has seen dramatic change in speech, but its formal written standard (文言 wenyan, “Classical/Literary Chinese”) has remained remarkably stable for roughly two millennia, only yielding to a vernacular written norm (白話 baihua) in the 20th century.

Spoken comprehension, then and now

English as spoken language has change over time, but luckily smart people have deftly cleaved it’s transitions into bitesize periods, or at the very least crudely chopped into the sort of chunks that dog food commercials boast about. The first of these is Old English, born between the 8th and 11th centuries. To the untrained modern person, it is essentially gobbledegook, even in its written form. Middle English of use during the 14th century is marginally better, although those of us who have ever had Chaucer recited at them by a mad man hanging upside down from a classroom girder would like to stress the word marginally. Shakespeare, unsurprisingly given the sheer volume of novel words he introduced in written form to the language, marks the beginning of Early Modern English. Whilst it is reasonably easy to read, it would have been difficult for a time traveller to understand as English was still waiting for the Great Vowel Shift, which not only radically altered the sound of vowels, but also ruined the rhymes of Shakespeare’s poems. After the 18th century, it is safe to assume that our time traveller would have no problem understanding the words coming out of people’s mouths, although they may be flummoxed by some of his.

The point here, is that the linguistic challenges of temporal travel for an English speaker are born out of English’s tendency to mutate and absorb numerous influences.

Chinese is a little different. While similar in terms of spoken communication – the spoken language of the 5th century (Middle Chinese era) differed significantly from Modern Chinese, and even that of the 15th century would be difficult, even without accounting for regional, dialectical differences, for a modern day Taiwanese person to understand – the written standard (Classical Chinese) has been a stable, supradialectical medium since antiquity thanks to imperial exams. In essence, while people spoke local variants, they all (well those who could write) wrote the same. This is the writing known as Wenyan (文言) which was only replaced by baihua (白話) in the early 20th century as the result of the New Culture/May Fourth movement of the 1910s – 20s.

But could our modern day time traveller understand this written form? Well, that depends. As stated, wenhua has been consistent for centuries, and as such it has been used for governance, medicine, scholarship, and letter writing into the early 20th century, much as Latin was used in European countries, but it is not easy to learn. Without schooling and practice it is unfathomable to modern day Chinese speakers. They can read the individual characters, but not understand the meaning of the condensed, somewhat elegant, and definitely irritating prose.

TL; DR

Situation English Speaker Chinese Speaker

Understand speech 500 years ago Hard but possible Exceedingly difficult

Understand speech 1500 years ago Impossible Impossible

Understand writing 500 years ago Challenging but possible (with training) Very possible (with training)

Understand writing 1500 years ago Mostly no Yes, if educated in Classical Chinese

English through time

Let’s have a look at how English has changed over the years. We’ll start with Old English c. 8th-11th c.) and a spot of Beowulf, a book I once foolishly tried to read at prep school simply because I liked the cover. I gave up on it quickly and have never looked back.

Hwæt! Wē Gār-Dena in geār-dagum,

Beowulf1

þēod-cyninga þrym gefrūnon,

hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon.

In modern English, this would be:

Lo, we have heard of Spear-Danes in days of yore, of folk-kings’ prowess, how the princes wrought deeds of valour.

As you can tell, the two appear to be completely unrelated, and I challenge anyone to claim they can read the original as fluently as the modern translation.

So, let’s move on to Middle English (c. 14th c.) and Geoffrey Chaucer, a renowned poet famed for his tales critiquing the Church, religion, and society as a whole. This particular extract was chosen by Mr. Ahern, and if it was good enough for me to learn at school, it’s good enough to use here:

Now, sire, and eft, sire, so bifel the cas

The Miller’s Prologue and Tale, Geoffrey Chaucer, 1476 (1st print edition)2

That on a day this hende Nicholas

Fil with this yonge wyf to rage and pleye,

Whil that hir housbonde was at Oseneye,

As clerkes ben ful subtile and ful queynte;

And prively he caughte hire by the queynte,

And seyde, “Ywis, but if ich have my wille,

For deerne love of thee, lemman, I spille.”

Which in modern English goes like this:

Now, sir, and again, sir, it so happened

That one day this clever Nicholas

Happened with this young wife to flirt and play,

While her husband was at Oseneye,

For clerks are very subtle and very clever;

And intimately he caught her by her crotch,

And said, “Indeed, unless I have my will,

For secret love of thee, sweetheart, I die.”

Instantly we can see that this is now far easier to understand, but there are enough words that we are unfamiliar with that we miss Chaucer’s playful use of language. When spoken rather than written, it is far harder to understand, so our time traveller would still be begging for subtitles.

And finally, in the late 16th to early 17th century we arrive at early Modern English and Shakespeare.

O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare, c. 15953

Ah, much easier to understand, or at least it appears to be. We need to remember that the Great Vowel Shift meant that Shakespearean English would not have sounded like modern English, and that’s before we get to the issue of the meaning of this frequently quoted but oft-misunderstood line. The issue being that while wherefore sounds to the modern ear like the word where, it actually means for what, or why4. Juliet is not asking for Romeo’s location, she is asking why he has his name, as if he had another not only would he smell as sweet, but their love would also be unimpeded.

Chinese through time

This will be harder for me to write and explain than it will be for you to understand. I am by no means a Chinese scholar. Hell, I can’t even read the poorly researched, populist, partisan drivel sponsored by pro-China companies that passes as the news in Taiwan and that is designed to be digestible by even the least educated people in the land, so bear with me as I attempt this.

So, let us head back in time to the late Spring and Autumn period, close to the Warring States period oof Chinese history for that is when Confucius lived (551–479 BCE) and his intellectual heirs compiled his teachings into the Analects (c. 475–221 BCE).

學而時習之,不亦說乎?

Confucius (Analects 論語 1.1)5

有朋自遠方來,不亦樂乎?

In modern Chinese this would be written as:

學習並按時溫習,不也是一件令人愉快的事嗎?

有朋友從遠方來,不也是很快樂的事情嗎?

Note how much longer the modern version is. In English, both translate as:

Is it not pleasant to learn with a constant perseverance and application?

Is it not delightful to have friends coming from distant quarters?6

A modern, educated reader can learn to read these sentences, as while the grammar is compact, it is consistent with modern Chinese. However, it must be noted that the reader would need to be taught how to understand them in their entirety.

Sticking with classical diction, we find ourselves in the 5th century/Eastern Jin period and we have a spot of poetry:

種豆南山下,草盛豆苗稀。

歸園田居 (其三) – Returning to the Fields,” No. 3 – 陶淵明 Tao Yuanming (365–427)7

晨興理荒穢,帶月荷鋤歸。

Which in modern Chinese reads as:

在南山腳下種豆;雜草茂盛,豆苗稀疏。

清晨起床整理荒地,月光下扛著鋤頭回家。

Or in English as:

I plant beans at the foot of the southern hills; the grasses thrive, the bean-sprouts thin.

At dawn I clear the wilderness; beneath the moon I shoulder my hoe and return.

This should be simple for a modern speaker to parse, however, that would not help them be understood in the 5th century when diction was quite different.

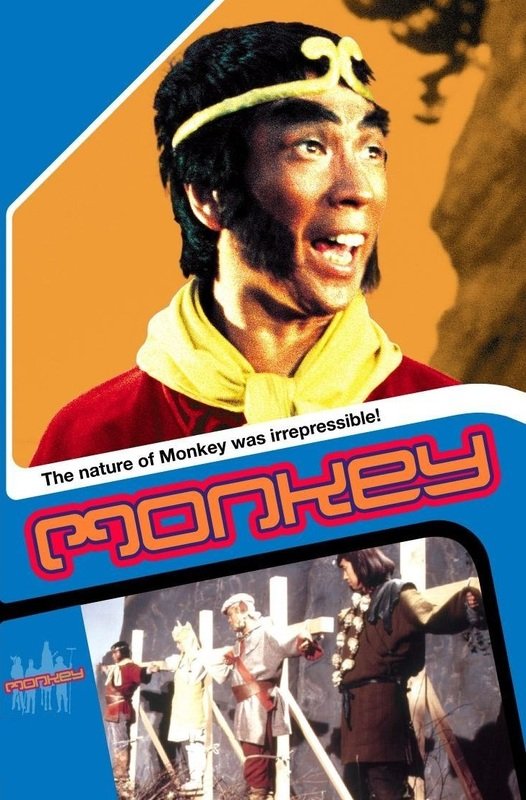

And finally we come to the rise of the modern vernacular in the 15th and 16th century with this extract from the Ming novel, Journey to the West (西遊記), better known as Monkey to Western audiences:

混沌未分天地亂,茫茫渺渺無人見。

Journey to the West, Chapter 1, Verse 18

自從盤古破鴻濛,開闢從茲清濁辨。

And again, in Modern Chinese:

混沌未開時,天地一片混亂,茫茫無人可見。

自從盤古打破元氣混沌,天地開闢後,清濁才開始分明。

And finally in English:

Before the primal chaos split, heaven and earth were a riot of confusion, vast and without witness. Since Pangu sundered the murk, creation has separated into the clear and the turbid.

Here the text represents an evolutionary link between Wenyan and baihua writing. It is a mixture of classical verse with the language as it was spoken at the time.

Why Classical Chinese Stayed Stable:

It was supradialectical, no matter where in China you came from its meaning remained constant, even if local dialects meant it was pronounced differently

The imperial exams fossilized style and grammar. Sadly, the adherence to strict rote repetition is still prevalent in the modern Taiwanese education system.

Logographic writing meant phonological change didn’t break orthography. In short, spelling changes didn’t occur; therefore, the language was less likely to change.

The May Fourth movement finally pushed vernacular writing into standard use. At this point regular people were finally able to read the news and literature and the language started to evolve more, despite the efforts of many to keep it the same.

Conclusion:

Whether a time traveller came from London or Taipei, they would have trouble communicating. In English, the written form is more problematic, whereas in Chinese the myriad dialects in use before the establishment of Modern Chinese would have been a greater obstacle.

- https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/eieol/engol/10 ↩︎

- https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/millers-prologue-and-tale ↩︎

- https://www.rsc.org.uk/romeo-and-juliet/about-the-play/famous-quotes ↩︎

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/wherefore-meaning-shakespeare ↩︎

- https://ctext.org/analects/xue-er ↩︎

- Legge, James. The Chinese Classics, Volume 1: The Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, and The Doctrine of the Mean. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1861. (Public domain) ↩︎

- https://fanti.dugushici.com/ancient_proses/70288 ↩︎

- https://zh.wikisource.org/zh-hant/%E8%A5%BF%E9%81%8A%E8%A8%98/%E7%AC%AC001%E5%9B%9E ↩︎

Further reading:

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Great Vowel Shift. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 05/11/2025, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Vowel-Shift

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Middle Chinese. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 05/11/2025, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Middle-Chinese-language

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Baihua. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 05/11/2025, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/baihua

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Chinese examination system. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 05/11/2025, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chinese-examination-system

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). May Fourth Movement. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 05/11/2025, from https://www.britannica.com/event/May-Fourth-Movement